Government mail service may be affected by the Canada Post labour disruption. Learn about how critical government mail will be handled.

Introduction to Canada

The Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus) is unique because it must live with humans or in their structures. It cannot survive in natural areas and cannot overwinter in cultivated fields in Canada.

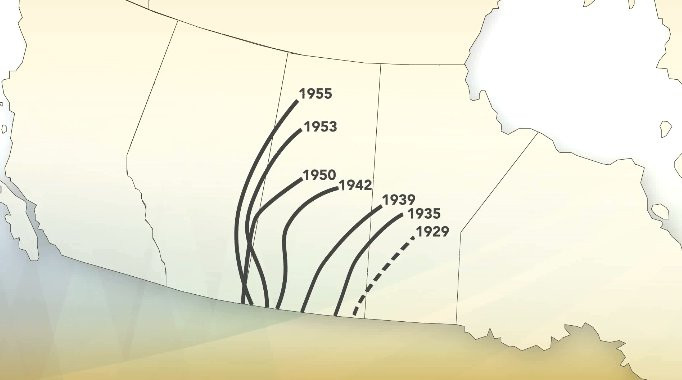

Norway rats are not native to North America but were introduced to the east coast around 1775. They gradually spread westward over most of the continent as North America became settled, farms were built closer together, and cultivated land began to dominate the landscape.

Rats entered Saskatchewan in the 1920s and extended their range to the northwest at about 24 km (15 mi) per year. Rats were first reported on the eastern border of Alberta in 1950, and would have continued to spread westward had it not been for a rat control program that halted their advance and continues to maintain an essentially rat-free province to date.

Figure 1. The spread of the Norway rat across the prairies starting in the 1920s.

1950 to 1953

Norway rats were first discovered on a farm in Alberta near Alsask, on the eastern border, during the summer of 1950. The discovery was made by field crews from Alberta Department of Health who were engaged in studies of sylvatic plague, a disease of Richardson's ground squirrel.

Although aware of the economic destruction caused by rats, provincial authorities were initially concerned that rats might spread plague throughout Alberta. Consequently, the Alberta government decided to halt, or at least slow, the spread of rats into Alberta In 1950. Responsibility for rat control was transferred from the Alberta Department of Health to the Department of Agriculture.

Agricultural Pests Act

The Agricultural Pests Act of Alberta (1942) authorized the Minister of Agriculture to designate as a pest any animal that was likely to destroy crops or livestock. The act further stipulated that every person and municipality had to destroy and prevent the establishment of provincially designated pests. Where pest control was not considered adequate, the provincial government could carry out the necessary measures and charge the costs to the landowner or municipality.

In this way, legislation that mandated control of pests by every person and at every level of government was in place before rats ever entered Alberta. That legislation became effective when rats were declared a pest in 1950. An amendment to the Act in 1950 further required that every municipality appoint a pest control inspector.

Rat Control Zone

Figure 2. Rat Control Zone in eastern Alberta

View larger image: Alberta Rat Control Zone

William Lobay, crop protection supervisor, originally conceived the idea of a control zone to prevent rats from spreading into Alberta. He was initially responsible for organizing, supervising and administering the program from 1950 to 1953.

Since the early 1950s, Alberta has maintained a Rat Control Zone (RCZ) along the eastern border with Saskatchewan. This 600-km long and 29-km wide swath of land runs from Cold Lake in the north to the Montana border in the south (Figure 2). Supported by government through funding and supplies, the 7 municipalities in the zone bear the most responsibility for rat control. In addition, farmers, counties, pest control officers and the government’s rat control staff help maintain Alberta’s rat-free status.

Public education

Figure 3. Provincial employees providing public education

Most people in Alberta had never been in contact with rats and did not know what they looked like or how to control them. Consequently, the government's initial response was to educate the public and get support from local governments and residents.

Preserved rat specimens were distributed to Alberta Agriculture offices to aid in the identification of rats in the 1950s. In 1951, 5 provincial employees whose primary responsibility was weed inspection provided training and assistance to municipal pest control inspectors. Personnel from the Saskatchewan Department of Health, familiar with rats and rat control, also assisted with training.

Conferences on rat control were held in 6 towns in eastern Alberta, and 2,000 posters and 1,500 pamphlets were distributed to grain elevator, railway station, school and post office staff, as well as private citizens.

Early control methods

Figure 4. Rat Control in Alberta pamphlet, 1951

The rat control pamphlet advocated the destruction of rats, the elimination of rat harborages and food supplies, and the rat-proofing of buildings – principles which are still valid and basic for rat control today. Recommended toxicants were red squill, antu, barium carbonate, zinc phosphide, 1080, thallium sulfate, arsenic, strychnine alkaloid and warfarin. Warfarin, the first anticoagulant rodent poison, was still a new and relatively untried toxicant in 1951.

In the fall of 1951, 30 rat infestations had been confirmed along 180 km of Alberta's eastern border. By 1952, rats were active along 270 km of the border. While most infestations were within 10 to 20 km of the border, rats had penetrated 50 to 60 km westward in 3 areas between Medicine Hat and Provost.

Alberta did not have the expertise to control rats and probably could not have developed the expertise in time to halt the movement of rats to the west. Consequently, a private pest control firm was contracted to control rats until Alberta Agriculture could develop an effective program.

From June 1952 to July 1953, some 63,600 kg of 73% arsenic trioxide tracking powder was used to treat 8,000 buildings on 2,700 farms (24 kg/farm; 8 kg/building). This took place within an area 20 to 50 km wide and 300 km long, between Medicine Hat and Provost. Tracking powder was blown underneath all permanent buildings within the control zone. While only permanent buildings were supposed to have been treated, some temporary structures were treated as well. Tracking powder was exposed in some areas where the treatment was haphazard or where temporary buildings were moved or torn down. Some residents were not informed that arsenic was being used. In addition, some were allegedly told that the tracking powder was harmful only to rodents. Consequently, some non-target poisoning of livestock, poultry and pets occurred for at least the first 2 to 5 years after treatment. As a precaution, Alberta Agriculture sent letters to all residents in the control zone each year until 1955, warning of the dangers to humans, livestock and pets.

The poison-proofing program was expensive, costing $152,670 for 1952-53, of which 74% was for tracking powder. The annual cost of rat control did not exceed this figure until 1978. Consequently, the poison-proofing program was discontinued because the arsenic poison too dangerous and the cost considered too high. However, the program apparently was effective; most infestations were confined to areas within 10 to 20 km of the border, and Alberta Agriculture was given the time to develop a rat control program.

1953 to 1959

During this period, Alberta’s Rat Control Program evolved into its current structure. Pest control inspectors were appointed by municipalities. Control was administered and supervised by local governments with co-ordination and support by the provincial government.

The southward spread of rats halted in 1953 when they reached the relatively uninhabited Cypress Hills. Rats continued to spread north until 1958 when they were stopped by the unpopulated and unbroken boreal forest near Cold Lake.

Then, as today, the 7 rural Alberta municipalities bordering Saskatchewan carried the major responsibility for rat control. Funding, however, was in dispute. These municipalities argued they were spending funds to protect the entire province from rats. Thus in 1954, Alberta Agriculture agreed to pay 50% of the salary and expenses of a full-time pest control inspector for each rural municipality along the eastern border. These pest control inspectors performed key tasks:

- checked every premise within the first 3 ranges (29 km) west of the border (Figure 2)

- distributed bait and established bait stations

- encouraged rat-proofing of buildings and the removal of rat harborage and food

- destroyed any rat infestations that were found

Public education

Figure 5. Poster released by the Alberta Department of Public Health circa 1948 (A17202b/ Provincial Archives of Alberta)

View larger image: You Can’t Ignore the Rat poster

To order copies of this photograph or poster, contact the Provincial Archives of Alberta.

Figure 6. Radio broadcasts were made on Alberta's ‘Call of the Land’ radio program

Public education and information about the program continued in the 1950s. Posters and brochures on rat control were widely distributed. Displays were presented at local fairs, picnics and rodeos, and talks were presented to schools, 4-H clubs, agricultural societies, chambers of commerce, and to just about anyone who would listen. Call of the Land, an Alberta Agriculture agricultural news program, began broadcasting in 1953 and was used to disseminate information on rat control.

Despite initial resistance, public interest and support for rat control was favorable, particularly from people who had rat infestations. As an example, 7 meetings were attended by almost 900 people in the Medicine Hat area during February 1956.

Enforcement actions

During this period, the Agricultural Pests Act made rat control mandatory. Property holders who failed to control rats and disregarded repeated encouragement and warnings from pest control inspectors could be served with an official warning. Failure to comply with the terms of the warning could result in a court action.

However, legal recourse was not used for several years until the public was educated in rat control. The first court case did not occur until 1955. In 1956, some 17 notices to control were issued and 3 court actions and convictions resulted. At that time, court cases were heard by a local magistrate who was usually a locally prominent citizen, often a merchant or postmaster. Therefore, rat control was enforced as well as supervised at the local level. The court actions apparently had the desired effect; no more than 7 notices to control rats have been issued in any year since 1956.

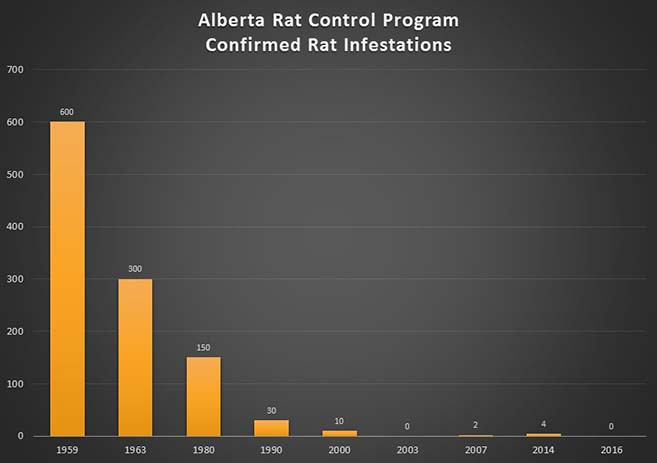

The number of known rat infestations in the border area of the provincial control zone increased rapidly from one in 1950 to 573 in 1955. The numbers varied between 394 and 637 during 1956 to 1959. After 1959, the numbers of infestations dropped dramatically (Figure 7). Hence, almost 10 years passed before an accumulation of training, experience and public education brought the rat problem firmly in hand.

The City of Lloydminster presented a special geographic problem for rat control as it straddles the Alberta-Saskatchewan border. Rat control in the Alberta portion of the city would have been difficult if there was no control in the Saskatchewan portion. This dilemma was resolved by orders in council by the governments of Alberta and Saskatchewan that declared Alberta’s Agricultural Pests Act of Alberta also applied to the section of Lloydminster on the Saskatchewan side of the border.

1960 to present

Rat control measures in Alberta have not changed much since 1960. Major differences today include a smaller workforce, fewer farmsteads, improved road systems, and better communications and control agents. Most rat control measures are performed by pest control inspectors hired and supervised by rural municipalities along the Alberta-Saskatchewan border. The provincial government's share of funding increased 60% in 1971, to 75% in 1973, and 100% in 1975. The number of premises inspected annually varies between 2,000 and 4,000.

After 1959, the number of infestations dropped dramatically; to the point where there are 1 to 5 infestations confirmed per year (Figure 7). The number of single rats that hitch rides on vehicles per year total more than the infestations now.

Figure 7. Confirmed infestations in the Rat Control Zone since 1959

Today, the Norway rat continues to be a declared pest under Alberta’s Agricultural Pests Act. While the province is responsible for the administration of the Act and the Rat Control Program, every person and municipality, both rural and urban, must take active measures to prevent the establishment of rats on their property. Rat infestations are eliminated as soon as possible by rodenticides or traps.

Farmers within the control zone are encouraged to prevent rat populations from breeding by eliminating rat food sources and possible shelters, among other methods. Find out more about rat prevention and control in Alberta.

Over the years, the governments of Alberta and Saskatchewan have shared information and resources to help control and eradicate this devastating pest. Saskatchewan initiated their own rat control program in 1963, which may have reduced the number of rats moving into Alberta. Find out more about Saskatchewan’s Rat Control Program.

Illegal to own rats as pets

Under the Act, it is illegal to import and sell rats in the province, or keep them as pets. A few white rats have been brought in by pet stores, biology teachers and well-meaning individuals who did not know it was unlawful to have rats in Alberta. The white rat or laboratory rat is a domesticated Norway rat. If white rats escaped captivity or were turned loose, they could multiply and spread throughout Alberta just like the wild Norway rat.

Consequently, white rats can only be kept by zoos, universities and colleges as well as recognized research institutions in Alberta. It is illegal for private citizens to keep any strains of rattus species of rats as pets, including hooded and white rats.

How Albertans can help

Hundreds of suspected infestations are reported each year by concerned citizens. The Alberta government encourages citizens to report rat sightings. In 2020 an email address – [email protected] – replaced the previous dedicated rat reporting phone line. Albertans can now send pictures and location information straight from their smartphones or computers. They can still report rat sightings by phone to the Ag-Info Centre at 310-FARM (3276).

Since most ‘rats’ reported in Alberta today are in fact other mammals, public education efforts are directed toward the identification of rats and rat signs. In addition, the success of Alberta’s Rat Control Program is often reported by provincial, national and international media. This serves as a reminder to residents that rat control is still an important program in the province.

After many years, rat control has become routine and is a source of pride to the citizens of Alberta. However, the problem is not solved; personnel involved in rat control must continually guard against complacency. Rats can spread throughout Alberta just as easily today as they could in the past. Find out how rat populations are prevented and controlled in Alberta today.

Figure 8. Poster used by Alberta Agriculture circa 1990

Acknowledgements

Alberta’s Rat Control Program has been successful thanks to the concern and effort of thousands of citizens and hundreds of pest control inspectors.

The following individuals have contributed immeasurably to the success of the program:

- William Lobay, supervisor of crop protection, had the imagination to conceive the program in 1950 and directed the program from 1950 to 1953.

- Arthur M. Wilson continued to support the program as field crops commissioner and later as director, plant industry division.

- Joseph B. Gurba, the first full-time permanent employee on the Rat Control Program, developed, coordinated and supervised the program from 1953 to 1982.

- John Bourne managed the Rat Control Program from 1971 until 2006, making many improvements.

- Phil Merrill took over the managing the program in 2010 and promoted and improved the program with his passion and knowledge for pest control until his retirement in 2020.

- Karen Wickerson and Garrett Girletz are the current rat and pest specialists overseeing the Rat Control Program.

Report a rat

If you see a rat, safely take a picture, note the location, and send us the information one of these ways:

Hours: 8:15 am to 4:30 pm (open Monday to Friday, closed statutory holidays)

- Email: [email protected]

- Toll free: 310-FARM (3276) (in Alberta)

- Phone: 403-742-7901 (outside Alberta)

- Phone your local bylaw Agriculture Fieldmen office.

It is illegal to own pet rats in Alberta.