Government mail service may be affected by the Canada Post labour disruption. Learn about how critical government mail will be handled.

Overview

Avian influenza viruses are common in wild birds, primarily waterfowl. Many strains of avian influenza viruses occur naturally in wild birds around the world, particularly:

- ducks

- geese

- shorebirds

When migrating waterfowl and shorebirds pass through Alberta, they can share their viruses with local wild birds which may not have the same level of immunity. In recent years, wild bird mortality is limited during spring migration but in some years is considerably higher during fall migration. Local mortality can continue into winter months among geese that stay on open (unfrozen) waters in southern Alberta.

The Alberta government conducts ongoing surveillance of the virus in wild birds and reports results to the national surveillance program.

Traditionally, avian influenza viruses did not cause disease in wild species but were able to spread and impact domestic poultry, including ducks, chickens and turkeys. These viruses are a significant concern for poultry producers and potentially pork producers. Since 2021/22 avian influenza viruses have been associated with mortality in a wide range of wild inland and marine waterbirds across North America. In Alberta we also saw significant mortality in striped skunks with avian influenza.

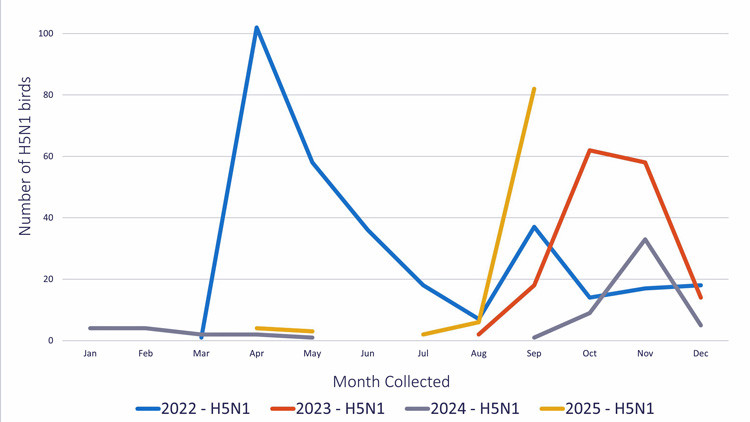

While we see cases of avian influenza confirmed in wild birds every year, fall 2025 was noteworthy for the increased number of sick and dead waterfowl, primarily geese, with highly pathogenic avian influenza. The virus poses very little threat to humans and is different than the human influenza viruses, but the primary risk is to farmed poultry.

Ongoing surveillance

January 2026

Following a relatively large number of of highly pathogenic avian influenza cases in wild geese and a few raptors throughout fall 2025, residual mortality continues in local areas. The problem is focused in southern Alberta, primarily along the Oldman and South Saskatchewan rivers from Pincher Creek to Medicine Hat. Mortality largely involves Canada geese congregated on unfrozen waters.

The extent of mortality is difficult to assess but is estimated to be about 1000 to 2000 dead geese cumulatively in December and January. In November 2025, the virus also was identified in 5 skunks that are assumed to have eaten infected birds. In previous years mortality decreased as winter progressed.

Image 1. Monthly H5N1 cases in wild birds tested from March 1, 2022 to January 1, 2026.

Surveillance history

Previous outbreaks

In Canada, avian influenza is a national reportable disease when it occurs in poultry. Outbreaks in domestic birds occur now and again, as happened in British Columbia and Ontario in 2015 and Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador in 2021-22. For more information, see:

Influenza viruses constantly change and resort their genetic material. Highly pathogenic (disease-causing) strains in poultry generally do not occur in wild birds.